Guardians of the heart: Reducing cardiotoxicity in cancer treatment

In the intersection of cardiology and oncology, the risks of cardiotoxicity from cancer treatments remain a pressing issue. Han Zhu, MD, assistant professor and director of the Stanford Translational Cardio-Oncology Program, leads research to mitigate these cardiac risks and improve patient outcomes during cancer therapies.

Zhu’s program focuses on reducing cardiotoxicity across a spectrum of cancer therapies, from traditional chemotherapy to newer immunotherapeutic and targeted approaches.

“The goal is to get patients’ hearts through their cancer treatments safely,” she emphasized.

In oncology, the term “permissive toxicity” refers to the understanding that all treatments come with risks. To mitigate these risks, Zhu and her team conduct rigorous research to identify safe dosage levels and biomarkers that indicate when to modify treatment regimens or initiate cardioprotective therapies. This proactive stance seeks to personalize therapies and minimize adverse effects while promoting overall treatment efficacy.

Diving into immunotherapy-induced myocarditis

One significant area of focus of Zhu’s research is immunotherapy-induced myocarditis, an inflammatory reaction of the heart that can occur in patients undergoing immunotherapeutic treatments. While this complication is rare, affecting less than 1% of patients, it can have devastating consequences, with a staggering 38-46% case fatality rate.

Zhu’s lab has made strides in understanding the mechanisms behind this severe side effect. By employing advanced technologies like single-cell multi-omics and T cell receptor sequencing, they investigated the immune response in patients who developed myocarditis. Their research revealed something surprising: T cells, vital for targeting tumor cells during immunotherapy, can become dysregulated and attack the heart instead.

In a recent study, Zhu and her team discovered that cytotoxic CD8 T cells exhibited abnormal activation patterns in patients suffering from myocarditis while correctly activated in a therapeutic context. Building on this, the lab conducted studies on genetically modified mice to delve deeper into immune cells’ role in heart inflammation.

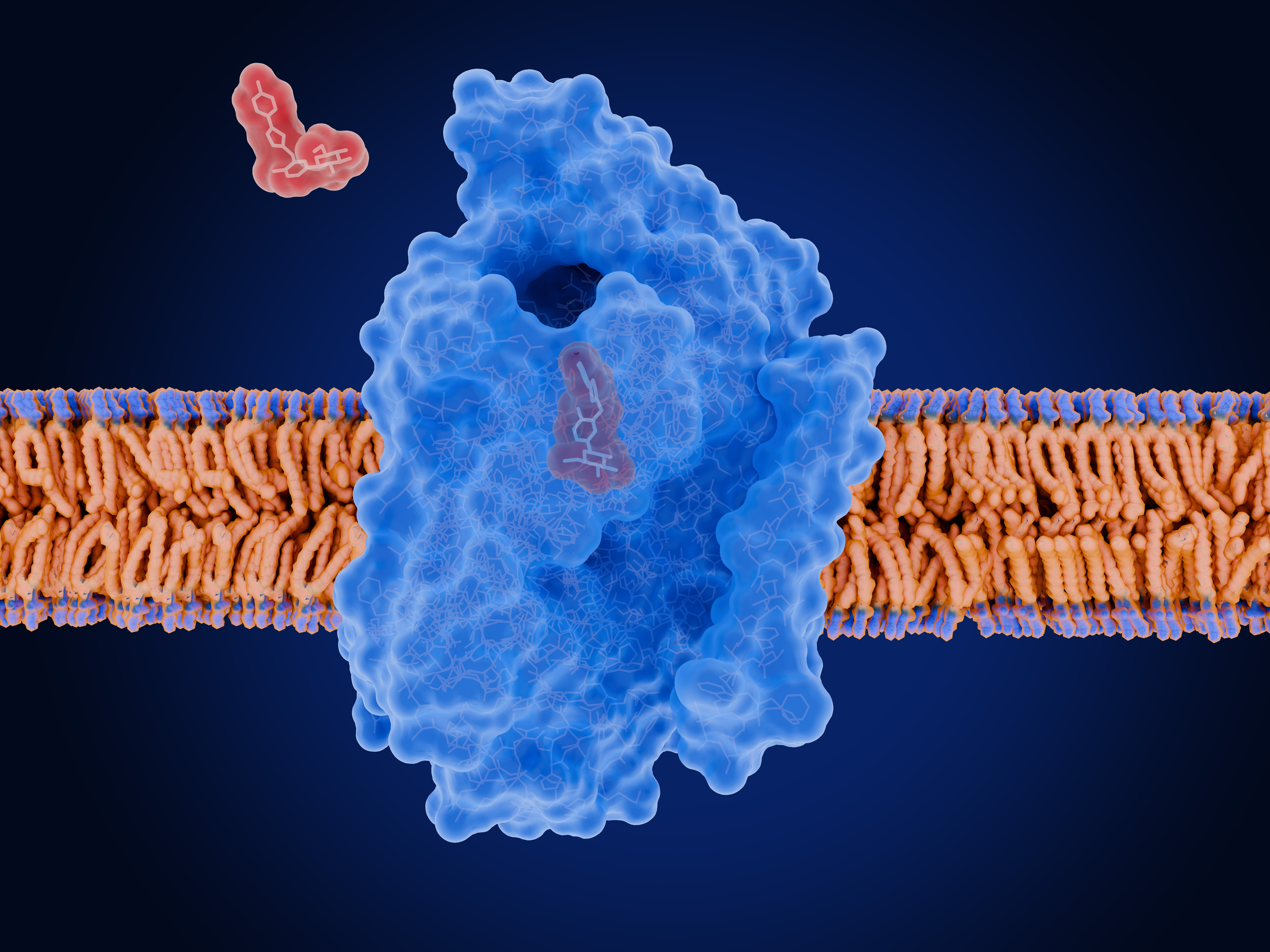

Surprisingly, they found that macrophages, white blood cells that get rid of microorganisms and dead cells, play a critical role in the development of myocarditis, necessitating a shift in research focus toward these immune cells. The group’s use of single-cell analysis in mice treated with immunotherapy led them to target the chemokine receptor CXCR3. They observed that inhibiting CXCR3 significantly reduced myocarditis risk and even resolved existing cases in their mouse models—a promising discovery with potential implications for clinical treatment protocols.

Future steps and implications

Looking ahead, Zhu aims to identify safe and effective CXCR3 inhibitors that mitigate myocarditis without broadly suppressing the immune system.

“We need a drug that is fast on, fast off,” she explained, highlighting the need for therapies that prevent debilitating side effects while maintaining a patient’s immune functionality.

Moreover, the potential applications of CXCR3 inhibition extend beyond cardiotoxicity. Collaborative efforts at Stanford suggest that targeting CXCR3 may benefit other organs affected by immunotherapy and can even preserve the immune response necessary for fighting tumors. Zhu’s research not only aims to protect the heart but could also enhance the overall effectiveness of immunotherapy.

“The collaboration between the Stanford Cancer Institute and the Cardiovascular Institute is really amazing,” she said. “We’ve had long-standing collaborations, and a lot of this research has stemmed from that.”

By Kai Zheng

February 2025

link